Philosophy of science and technology in support of political ecology

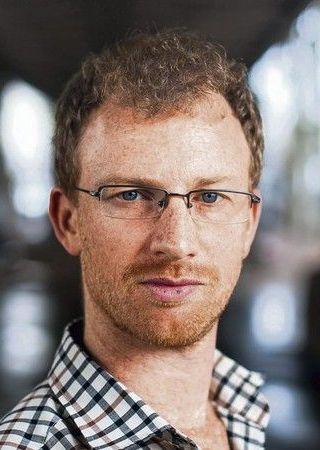

Fabrice Flipo, a philosopher of science and technology and researcher at Institut Mines Télécom Business School (former Télécom École de Management), has specialized in political ecology, sustainable development and social philosophy for nearly 20 years. Throughout the fundamental research that shapes his more technical teaching, he tries to produce an objective view of current political trends, the ecological impact of digital technology and an understanding of the world more broadly.

For Fabrice Flipo, the philosophy of science and technology can be defined as the study of how truth is created in our society. “As a philosopher of science and technology, I’m interested in how knowledge and know-how are created and in the major trends in technical and technological choices, as well as how they are related to society’s choices,” he explains. It is therefore necessary to understand technology, the organization of society and how politics shapes the interaction between major world issues.

The researcher shares this methodology with students at Télécom École de Management in his courses on major technological and environmental risks and his introductory course on sustainable development. He helps students analyze the entire ecosystem surrounding some of the most disputed technological and environmental issues (ideas, stakeholders, players, institutions etc.) of today and provides them with expertise to navigate this divisive and controversial domain.

Fundamental research to understand global issues

This is why Fabrice Flipo has focused his research on political ecology for nearly 20 years. Political ecology, which first appeared in France in the 1960s, strives to profoundly challenge France’s social and economic organization and to reconsider relationships between man and his environment. It is it rooted in the ideas of a variety of movements, including feminism, third-worldism, pacifism and self-management among others.

Almost 40 years later, Fabrice Flipo seeks to explain and provide insight into this political movement by examining how its emergence has created controversies with other political movements, primarily liberalism (free-market economics), socialism and conservatism. “I try to understand what political ecology is, and the issues involved, not just as a political party of its own, but also as a social movement,” explains the researcher.

Fabrice Flipo carries out his research in two ways. The first is a traditional approach to studying political theory, based on analyzing arguments and debates produced by the movement and the issues it supports. This approach is supplemented by ongoing work with the Laboratory of Social and Political Change at the University of Paris 7 Diderot and other external laboratories specializing in the subject. He works in collaboration with an interdisciplinary team of engineers, sociologists and political scientists to examine the relationship between ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) and ecology.

He also involves networks linked to ecology to expand this collaboration, works with NGOs and writes and appears in specialized or national media outlets. For some of his studies, he also draws on a number of different works in other disciplines, such as sociology, history or political science.

The societal impact of political ecology

“Today political ecology is a minor movement compared to the liberal, socialist and conservative majorities,” says the researcher. Indeed, despite growing awareness of environmental issues (CoP 21, development of a trade press, energy transition for companies, adopting a “greener” lifestyle etc.) the environmental movement has not had a profound effect on the organization of industrialized human societies, so it needs to be more convincing.

This position makes it necessary to present arguments in its minority status on the political spectrum. “Can political ecology be associated with liberalism, socialism or even conservatism?” asks the researcher. “Although it does not belong to any of the existing currents, each of them tries to claim it for their own.”

More than just nature is at stake. A major ecosystem crisis could open the door for an authoritarian regime seeking to defend the essential foundation of a particular society from all others. This sort of eco-fascism would strive to protect resources rather than nature (and could not therefore be considered “environmentalism”), pitching one society against another. Political ecology is therefore firmly aligned with freedom.

To stay away from extremes, “the challenge is to carry out basic research to better understand the world and political ideas, and to go beyond debates based on misunderstandings or overly-passionate approaches,” explains Fabrice Flipo. “The goal is to produce a certain objectivity about political currents, whether environmentalism, liberalism or socialism. The ideas interact with, oppose, and are defined by one another.”

Challenging the notion that modernity is defined by growth and a Cartesian view of nature, the study of political ecology has led Fabrice Flipo to philosophical anthropological questions about freedom.

Analyzing the environmental impact of digital technology in the field

Political ecology raises questions about the ecology of infrastructures. Fabrice Flipo has begun fieldwork with sociologists on an aspect of digital technology that has been little studied overall: the environmental impacts of making human activities paper-free, the substitution of functions and “100% digital” systems.

Some believe that we must curb our use of digital technologies since manufacturing these devices requires great amounts of energy and raw materials and the rise of such technology produces harmful electronic waste. But others argue that transitioning to an entirely digital system is a way to decentralize societies and make them more environmentally-friendly.

Through his research project on recovering mobile phones (with the idea that recycling helps reduce planned obsolescence) Fabrice Flipo seeks to highlight existing solutions in the field which are not used enough, with priority being given to the latest products and constant renewal.

Philosophy to support debates about ideas

“Modernity defines itself as the only path to develop freedom (the ability to think), control nature, technology, and democracy. The ecological perspective asserts that it may not be that simple,” explains the researcher. “In my different books I’ve tried to propose a philosophical anthropology that considers ecological questions and different propositions offered by post-colonial and post-modern studies,” he continues.

Current societal debates prove that ecological concerns are a timely subject, underscore the relevance of the researcher’s work in this area, and show that there is growing interest in the topic. Based on the literature, it would appear that citizens have become more aware of available solutions (electric cars, solar panels etc.) but have been slow to adopt them. Significant contradictions between the majority call to “produce more and buy more” and the minority call encouraging people to be “green consumers” as part of the same public discourse make it difficult for citizens to form their own opinions.

“So political ecology could progress through an open debate on ecology,” concludes Fabrice Flipo, “involving politicians, scientists, journalists and specialists. The ideas it champions must resonate with citizens on a cultural level, so that they can make connections between their own lifestyles and the ecological dimension.” An extensive public communication, to which the researcher contributes through his work, coupled with a greater internalization and understanding of these issues and ideas by citizens could help spark a profound, far-reaching societal shift towards true political ecology.

Political ecology: The common theme of a research career

A philosopher of science and technology, Fabrice Flipo is an associate research professor accredited to direct research in social and political philosophy and specializes in environmentalism and modernity. He teaches courses in sustainable development and major environmental and technological risks at Télécom École de Management, and is a member of the Laboratory of Social and Political Change at the University of Paris Diderot. His research focuses on political ecology, philosophical anthropology of freedom and the ecology of digital infrastructures.

He is the author of many works including: Réenchanter le monde. Politique et vérité “Re-enchanting the world. Politics and truth” (Le Croquant, 2017), Les grandes idées politiques contemporaines “Key contemporary political ideas” (Bréal, 2017), The ecological movement: how many different divisions are there? (Le Croquant, 2015), Pour une philosophie politique écologiste “For an ecological political philosophy” (Textuel, 2014), Nature et politique (Amsterdam, 2014), et La face cachée du numérique “The Hidden Face of Digital Technology” (L’Echappée, 2013).